My song Another Woman from the Pulse album appeared in Season 7, episode 6 of the CW series The Flash during 2021. Short but sweet.

My song Another Woman from the Pulse album appeared in Season 7, episode 6 of the CW series The Flash during 2021. Short but sweet.

The two tunes below were intended for the second Pulse album, Reach For The Sun, which never saw the light of day.

Both were written while the original six-piece band was together but weren’t arranged and recorded until 1969 during the transition period to a four-piece group that included second guitarist Harvey Thurott along with Beau Segal, Paul Rosano and Peter Neri.

Sometime Sunshine was the only tune on which Peter and I collaborated in Pulse. Peter wrote the main part of the song in late 1968, during a hiatus from the band for several months. When he came back in late ’68/early ’69 he had written a plethora of outstanding tunes that included Too Much Lovin’ (the Pulse album opener), Hypnotized, Garden Of Love and Days Of My Life (another unreleased gem), among others.

Sometime Sunshine was one of the band’s favorites of these tunes but Peter had no bridge for it. In early 1969 I had a song fragment that I believed would work in the middle of the tune. We tried it and somehow we made it happen in that little rehearsal shed at the back of the parking lot at Syncron Studios, our home base.

The song also became a showcase for the contrasting guitar tones and styles of Peter (Guild) and Harvey (Strat) as you can hear in the middle section call and answers between the two. And it was one of the highlights of the four-piece band’s live set.

Peter sang the middle section and I joined him in unison and harmony, one of my first recorded vocals.

The other tune, Heaven Help Me was one of my early compositions. At that time, I couldn’t pull off the opening acoustic and voice section of the tune so I taught the melody and changes to Peter, who developed the fingering style acoustic part and sang the melody exactly as I wanted it. I always thought that was amazing.

I sing the middle section, which still included Richie Bednarczyk on Steinway Grand, which attests to this being recorded during the transition, and Peter and I sing in unison mostly on the third section, which concludes the 7-minute tune.

An interesting side note on this song:

A license to use the song in a film by a Yale student was granted for an undisclosed (by my manager) sum of money. In fact, I didn’t even hear about this until weeks later when one of my fellow band mates mentioned it. When I went into the office of my manager/producer/publisher, he looked sheepishly at me, feigning disbelief that I didn’t know. He wouldn’t tell me for what the granting of the song’s rights were sold. Eventually, I was handed a check for $100, not an insignificant sum in the late ’60s, but for some reason I always felt it wasn’t commensurate with what it should have been.

One of the things that made me feel this was that when my manager’s accountant handed me the check he smirked and sarcastically remarked that I didn’t deserve to receive that much! Ah, the music business. Yet another familiar tale.

Anyways, I always liked both of these tunes and they were an indicator of where the band was headed. Unfortunately, this version of Pulse was no more after December of 1970. That then led to the New York-based Island.

Island was a trio formed after the final breakup of Pulse, a Connecticut rock group of the late 1960s with a self-titled album on Poison Ring.

Before moving on to Island, though, a little background on the second version of Pulse, a four-piece group, which had changed the direction of the original six-piece band from almost strictly blues-rock to other styles, including country blues, country rock and pop, but still a hard-driving unit.

In the spring of 1970 after the departure of lead singer Carl Donnell from the original six-piece, a variety of lineups were tried until it was settled on Peter Neri, lead guitar and vocals, Paul Rosano, bass and vocals, and Beau Segal, drums and backup vocals, all staying on and the addition of Harvey Thurott, a second lead guitarist and singer/songwriter joining the band.

The group lasted until December, having parted ways with Doc Cavalier and Syncron Studios, the going was tough in Connecticut. Harvey left the band, and Peter, Paul and Beau moved into New York to try to land a record deal.

In New York, the band went even more in a singer/songwriter, pop-rock direction. We had virtually nothing except our equipment when we moved in and a ton of song ideas. We rehearsed in a loft in the mid-20s on the West side between Fifth and Sixth Avenues that Peter and Beau rented and lived in and literally auditioned in the offices of a number of prominent management agencies, including Michael Jeffries, who managed McKendree Spring, Albert Grossman-Benet Glotzer, who represented a plethora of artists such as Dylan, Todd Rundgren, The Band and many others, and even Sid Bernstein, who wanted to set up a showcase for us in the Village.

We settled on doing business mainly with Grossman-Glotzer and in particular Sam Gordon who ran their publishing arm. He promptly signed us to a publishing deal and set up all kinds of studio time.

By the way, the photo above is of the second Pulse with Harvey since I have virtually nothing from the Island era. So 3/4 of the photo is Island.

We recorded most of our tunes at the old Capitol Studios in midtown, which was a cavernous room used for orchestras and musical comedy soundtrack recordings mostly, but the song here was done at Blue Rock in the Village, which is no longer around. A nice studio though. There are some photos of it in the video as well as one of Capitol.

As an added touch to this session, Sam Gordon got Todd Rundgren to come down and help engineer/produce it as a favor. We had produced the sessions at Capitol ourselves. The Blue Rock session is undoubtedly the best sounding of all the Island recordings. Rundgren had just released Something/Anything? and we would have loved to have him as our producer but he was being courted by some heavy hitters such as the New York Dolls and Grand Funk Railroad, both of whom seemingly gave him big paydays. Todd was quiet that afternoon but very easy to get along with and did a masterful job for us.

One thing I recall other than the session itself was that we literally ran into or rather walked into and met Astrud Gilberto, the Brazilian singer, who was checking the studio out for a possible location for her next album. Charming and quite beautiful.

Where Am I Going? was the first track we recorded that day and we were all quite pleased with it, still am. We got a particularly good drum sound on the track for Beau’s semi-busy but appropriate parts and everything worked out as planned from the vocals — I sang lead, Peter harmony — to Peter’s guitar parts and a piano part added by Barry Flast, whom we had met at Gordon’s Publishing offices.

The song followed our trend of writing and playing in a pop style. I recall getting the initial idea for it while walking around the city, notably the intro vocal and a piano playing straight fours. I used to love walking around New York on my own and often would trek from Chelsea, where I lived, to the East Village and back, with melodies and chord changes flying through my head, a great way to come up with musical ideas

<>

Days Of My Life was a track recorded after the first Pulse album was finished and was intended for a second album from the original six-piece group based in Wallingford, Conn., at Syncron Studios.

The tune was written by Peter Neri and indicated his development as a writer. Peter had a wealth of material during this period and Days Of My Life was one of his best compositions to date. It showed off the band’s playing in a jazzier blues style along with Carl Donnell’s accomplished vocals and the band’s intricate arrangement of the track, always spearheaded by drummer Beau Segal.

The tune was written by Peter Neri and indicated his development as a writer. Peter had a wealth of material during this period and Days Of My Life was one of his best compositions to date. It showed off the band’s playing in a jazzier blues style along with Carl Donnell’s accomplished vocals and the band’s intricate arrangement of the track, always spearheaded by drummer Beau Segal.

We all make significant contributions to this track from Peter’s driving rhythm guitar to Jeff’s outstanding harp fills and solo to Richie’s keyboard layers. We were all very much involved in the construction of this one.

The tune was recorded in 1969 and is one of the best of the unreleased tracks by the band. It’s hard to say how many tracks are in the can that never saw the light of day, but it has to be in the 15 to 20 range but probably higher. Check out the video below.

Thanks For Thinking Of Me But It’s Alright is the closing track of Side 1 from the self-titled Pulse album from 1969. After it was written and we arranged it in late 1968, it was also almost always Pulse’s opening tune in concert.

The group Pulse was based in New Haven, Connecticut, more specifically Wallingford at Syncron Studios soon to become Trod Nossel, which is still operating, and managed and produced by Doc Cavalier. The first version of the band was a six-piece. We started rehearsing in January, 1968 and were together until almost mid-1970. There was a four-piece group for the remainder of 1970.

The personnel: Carl Donnell (Augusto), vocals, guitar; Peter Neri, lead guitar, vocals; Beau Segal, drums; Paul Rosano, bass, background vocals; Jeff Potter, harp, percussion; Rich Bednarzcyk, keyboards.

The album was recorded in 1968 and early 1969, this track as stated probably late ’68. It was written by our drummer Beau Segal. We were huge fans of the Butterfield Blues Band, one of our main influences at the time, and we had seen them a number of times at the Cafe Au Go Go in New York and the Psychedelic Supermarket in Boston as well as the Oakdale Theatre in Wallingford.

The album was recorded in 1968 and early 1969, this track as stated probably late ’68. It was written by our drummer Beau Segal. We were huge fans of the Butterfield Blues Band, one of our main influences at the time, and we had seen them a number of times at the Cafe Au Go Go in New York and the Psychedelic Supermarket in Boston as well as the Oakdale Theatre in Wallingford.

Beau has said he took the lead line from a Butterfield tune he heard live. I know the one. Actually he embellished it a bit. If you listen to a live version of the tune by Butter it doesn’t have the chromatic ascent or the closing phrase that bounces off a minor third. And in fact, it’s not a Butterfield composition.

Butter was covering a Little Walter tune. Everything’s Gonna To Be Alright (1959). Butter’s version changed several times over the years. The only studio track I’ve heard is from an early session on the Original Lost Elecktra Sessions, which pre-dates the first Butterfield Band album.

It didn’t start with Little Walter either. The line was used by Elmore James in his Dust My Blues from 1955 as his closing solo. There are probably other examples from that time frame.

If you dig deeper you’ll hear the line as a part of the vocal melody on the bridge of Robert Johnson’s Kind Hearted Woman Blues, and the line is the basis for the main melody in Johnson’s Sweet Home Chicago. Wonder where he heard it if he didn’t originate it himself.

This stuff is fascinating, the Blues tradition. It’s reminiscent of the folk tradition in which entire chord structures and melodies of existing tunes were continually updated with new lyrics, particularly in the ’50s and early ’60s.

Going forward, it pops up in a number of other unusual places. In 1970, Atco Records released Live Cream, which included a studio outtake Lawdy Mama. The original Cream version of this song was a shuffle and included the same lead line. The outtake on Live Cream sees the track changed to a straight rock feel with the line still used but stretched out a bit.

However, many of us have heard this line hundreds of times on a slightly different track. The group ditched the Lawdy Mama version of the song when Felix Pappalardi was brought in to produce and his wife, Gail Evans, wrote new lyrics creating the tune Strange Brew. I never recognized the similarity until I heard the shuffle version of Lawdy Mama by Cream on a grey market item.

Eric Clapton would use the line again to good effect in his outstanding version of Sweet Home Chicago on the Sessions For Robert J album (2004). And so it goes.

The Butterfield Band was and remains one of my favorite groups of all-time and is sorely underappreciated. Thanks For Thinking Of Me was our tip of the hat to them, one of our major influences.

Christine Ohlman hasn’t really been away. In the past five years, she has continued to work with her band Rebel Montez and as a singer for the Saturday Night Live Band, and released the retrospective Re-Hive last year.

But The Deep End, released this month, is her first record of new material since Strip in 2004. It is certainly worth the wait. A collection of bluesy and soul-infused rockers and ballads with emotional, heartfelt lyrics of love and loss, The Deep End is Ohlman’s most complete and accomplished work.

But The Deep End, released this month, is her first record of new material since Strip in 2004. It is certainly worth the wait. A collection of bluesy and soul-infused rockers and ballads with emotional, heartfelt lyrics of love and loss, The Deep End is Ohlman’s most complete and accomplished work.

The album benefits from an impressive cast of guests who each add something special. Al Anderson plays guitar on two tunes, including the title track, Dion, Ian Hunter and Marshall Crenshaw each sing duet vocals with Chris, and Levon Helm, G.E. Smith, Eric “Roscoe” Ambel, Catherine Russell, Paul Ossola and Andy York, guitarist from the John Mellencamp Band who also produces with Chris, are among the many contributors.

Chris and her band will debut the album at Cafe Nine in New Haven on Saturday, Nov. 14.

Chris sets the scene on the opener, There Ain’t No Cure, a gritty, infectious rocking track that features York on lead guitar and Hunter adding a duet vocal. The title track, one of Ohlman’s best compositions, follows with its Latin feel in the verse, interesting melodic twists in the chorus and telling lyrics that speak of loss, something Chris has endured in these past five years losing her mate and producer Doc Cavalier and longtime guitarist and collaborator Eric Fletcher. Anderson provides the lead work on the track in his signature country-blues style.

All the uptempo material is a delight. The grooves are deep and the playing exemplary. Ohlman is in fine form vocally throughout, bringing her unique soulful delivery that ranges from smooth as glass to rough and raspy. Among them — Love Make You Do Stupid Things, driven by Ambel’s chord-flavored lead style, the country-rock feel of Love You Right, again with Anderson, Bring It With You When You Come, which sees Rebel Montez guitarist Cliff Goodwin take a fiery, spitting solo, and Born To Be Together, on which Goodwin is again featured this time playing off the melody through what sounds like a Leslie speaker — are all highlights. Continue reading Return of the Beehive Queen

Earlier this summer, I saw Taj Mahal in concert with Bonnie Raitt on the impressive Bon Taj Roulet tour, the third time I’ve seen Taj.

The second time was in the spring of 1969 at the improbable club in New Haven, the Stone Balloon, fashioned after Greenwich’s Village’s Cafe Au Go Go.

The second time was in the spring of 1969 at the improbable club in New Haven, the Stone Balloon, fashioned after Greenwich’s Village’s Cafe Au Go Go.

As mentioned in a post on Jethro Tull, who had played the club in February, ’69, the Balloon wasn’t open long, less than a year, but booked a plethora of rising stars from Tull to Taj to Neil Young. Quite a venue situated under a Pegnataro’s Supermarket with a back entrance from the super’s parking lot.

Taj had released two albums by this time, his self-titled debut and the classic Natch’l Blues, which was released the previous summer. He was touring with his original band that included the incomparable Jesse Ed Davis on lead guitar, Chuck Blackwell on drums and bassist Gary Gilmore.

The Stone Balloon was tiny. We went to see them on a Saturday night, some weeks after the Tull show, and Taj and his band were in fine form playing a mix of tunes from the first two albums. They were not as loud as Tull (not that I didn’t like Ian Anderson & Co.), instead perfectly suited to the room size and Davis was mesmerizing.

Of course, Taj wasn’t too shabby either. He had a beautiful take on modern country blues with his unique and refreshing originals mixed with classics like Good Morning Little Schoolgirl, Corrina and You Don’t Miss Your Water (‘Til Your Well Runs Dry). Continue reading Concerts Vol. 9: Taj Mahal

I’ve known Chris Ohlman for more than 40 years, but unfortunately have only seen her perform a handful of times. And some of those were when we were on the same bill in different groups at charity events.

I caught The Beehive Queen and her remarkable band Rebel Montez Saturday night at Cafe Nine, a tiny club that might hold 200, in New Haven, Connecticut. Chris showed why she is one of the state’s legendary R&B/soul singers as I watched her play the first of two 90-minute sets that included original tunes from each of her five albums and a number of meticulously chosen covers that not only put her vast talents on full display but also carried a sense of blues and soul history.

I caught The Beehive Queen and her remarkable band Rebel Montez Saturday night at Cafe Nine, a tiny club that might hold 200, in New Haven, Connecticut. Chris showed why she is one of the state’s legendary R&B/soul singers as I watched her play the first of two 90-minute sets that included original tunes from each of her five albums and a number of meticulously chosen covers that not only put her vast talents on full display but also carried a sense of blues and soul history.

One of the first groups Chris sang with in the late ’60s was called Fancy, which included her brother Vic Steffens and was based out of Wallingford, CT at Syncron Studios, later Trod Nossel, managed by Doc Cavalier. In the ’70s, she fronted the ultra popular and ultra hot regional act The Scratch Band, which also featured G.E. Smith, later a leader of the Saturday Night Live Band, and bassist Paul Ossola, also with SNL. Chris as well has been a singer with the SNL Band since the early ’90s. Continue reading The Beehive Queen

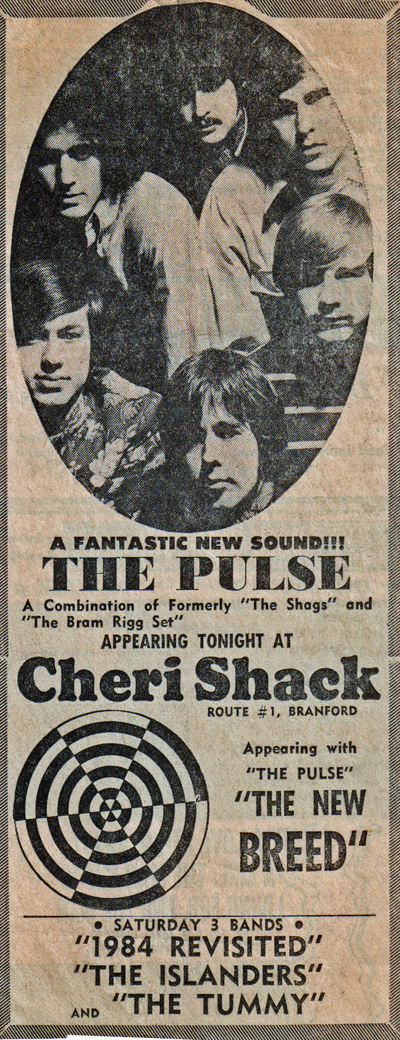

To recap part 2: At the end of the summer of 1967, two popular New Haven-based bands broke up at the prodding of manager/producer Doc Cavalier, who owned Syncron Studios (later Trod Nossel) in Wallingford. Three members from the Shags and three from the Bram Rigg Set joined to form The Pulse (the actual original name was The Pulse of Burritt Bradley). But after a failed single released on ATCO, the bubblegum confection Can-Can Girl, the group broke up after about six months. Pulse, a blues-rock outfit emerged with now four members from Bram Rigg Set, one lone survivor of the Shags and a new addition.

In January, 1968, Pulse started rehearsing in earnest to play some live dates and start recording its first album. The first gig was to be at a small club in Watertown, the Shack. We used to rehearse in what was called the Shed in back of Syncron Studios. The rehearsal room was an unfinished concrete-floored area no larger than a two-car garage with 2×4 framing exposed on the first floor of what looked like an old barn. This was perhaps the most dangerous place I’ve ever rehearsed, yet we carried on in the Shed for 2-plus years as Pulse.

In January, 1968, Pulse started rehearsing in earnest to play some live dates and start recording its first album. The first gig was to be at a small club in Watertown, the Shack. We used to rehearse in what was called the Shed in back of Syncron Studios. The rehearsal room was an unfinished concrete-floored area no larger than a two-car garage with 2×4 framing exposed on the first floor of what looked like an old barn. This was perhaps the most dangerous place I’ve ever rehearsed, yet we carried on in the Shed for 2-plus years as Pulse.

The danger lay in the ceiling, which was probably less than a foot above everyone’s heads. In fact, there was no ceiling, instead it was the foil side of insolation tucked in between the framing. So, if you happened to lift the neck of your guitar a little too high as when you were taking if off and your hands were touching the strings, you were in for a maximum jolt of electricity, the kind that tenses your entire body. I’ve had a few of those in my days, several from the Shed and it is as you may know no fun and rather scary. Still, we persevered.

Soon after forming, we added a sixth member, Jeff Potter, who played a mean blues harp and also added percussion with a conga drum and eventually occasional keyboards. Ray Zeiner, the keyboard player from the Wildweeds, had recommended him. Jeff and Ray lived next door to each other right down on the Connecticut River up near Hartford. Those houses are no longer there since the area flooded every so often. The Weeds had recently come into the fold with Doc (via their terrific single No Good To Cry) and Jeff had grown up and gone to Windsor High with Al Anderson and other members of the band.

Soon after forming, we added a sixth member, Jeff Potter, who played a mean blues harp and also added percussion with a conga drum and eventually occasional keyboards. Ray Zeiner, the keyboard player from the Wildweeds, had recommended him. Jeff and Ray lived next door to each other right down on the Connecticut River up near Hartford. Those houses are no longer there since the area flooded every so often. The Weeds had recently come into the fold with Doc (via their terrific single No Good To Cry) and Jeff had grown up and gone to Windsor High with Al Anderson and other members of the band.

Jeff added an element we needed and loved. The band was influenced by the great blues-rock groups of the times and in ’67-’68 that meant Paul Butterfield, Cream, Jimi Hendrix, John Mayall and others. So the lineup was Carl Donnell (Augusto), lead vocals and rhythm guitar, Peter Neri, lead guitar and vocals, Rich Bednarzck, keyboards, Paul Rosano, bass, Beau Segal, drums and Jeff.

We set out putting together two sets worth of material that included some unusual covers and what few original tunes we had at the time. We chose cover material that was not the usual fare for local bands in the same vein as the Bram Rigg Set, which always played songs no one else touched. This was largely influenced by Beau and when Bram Rigg was together lead singer Bobby Schlosser. Continue reading CT Rock ‘n Roll: Pulse, Part 3

I touched on a sliver of Connecticut Rock ‘n Roll in the ’60s in a previous post. Here is a little more of the story, particularly to clear up some misconceptions and inaccuracies that have been on the web for a long time.

Pulse was a group formed from the ashes of two bands managed by Doc Cavalier, who owned Syncron Studios in Wallingford, later Trod Nossel. One was the Bram Rigg Set (left), who had formed in 1966 and had a single on Kayden, I Can Only Give You Everything, the other the Shags, who had enjoyed great popularity in New Haven and the state for several years with singles such as Wait And See and Hey Little Girl. Both broke up in the summer of 1967.

Pulse was a group formed from the ashes of two bands managed by Doc Cavalier, who owned Syncron Studios in Wallingford, later Trod Nossel. One was the Bram Rigg Set (left), who had formed in 1966 and had a single on Kayden, I Can Only Give You Everything, the other the Shags, who had enjoyed great popularity in New Haven and the state for several years with singles such as Wait And See and Hey Little Girl. Both broke up in the summer of 1967.

The break-ups were motivated by Doc to form one stronger group from the two. I had been with the Bram Rigg Set for only about six months and toward the end of that time the band was fracturing. In 1967, our lead singer Bob Schlosser was already living in Rhode Island and by the summer we were not rehearsing as a full band and usually only playing on weekends. The Shags had several regional hit singles to their credit but their popularity was waning a bit.

The first version of the band, which was called The Pulse, note the subtle difference, was made up of three members of the Shags and three from the Bram Rigg Set. From the Shags – Carl Donnell, vocals and guitar, Tommy Roberts; vocals and guitar and Lance Gardiner, bass; from Bram Rigg – Beau Segal, drums, Peter Neri, guitar and Rich Bednarcyk, keyboards.

There are a couple of interviews out there that say this group had two bass players and I was one of them. That’s ridiculous, there were never two bass players. I never rehearsed with this version of the band. Since I was going to school in Boston, first to Boston University and then Berklee School (later College) of Music, I was just not available. And I’m sure Roberts wanted Lance in the band. That was fine with me at the time, despite my missing playing with Beau, Peter and Rich, with whom I’d formed a strong musical bond.

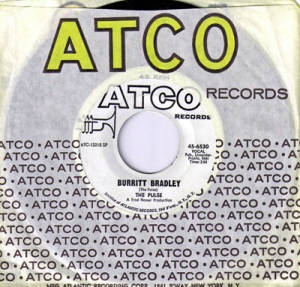

The Pulse went into the studio and started recording. From what I gleaned from Beau they were trying to come up with a single. They did and Doc sold it to ATCO, a subsidiary of Atlantic. Unfortunately the tune was Can-Can Girl, a bubble gum confection written by Roberts with the famous Can-Can melody on horns grafted into the middle of it. It quickly disappeared. The B side, a little more esoteric, was called Burritt Bradley. The single can still be found on eBay as well as record fairs for about $40.

This went on for about six months. I’m not sure what exactly precipitated the breakup but by the beginning of 1968 I received a phone call from Beau and he asked me if I wanted to be in Pulse, a new version of the group that would be a blues-rock based outfit. I said yes and ruined my college life, well to some extent. Because for the next four months or so I commuted on weekends to Wallingford for rehersals. But it was well worth it.

In fact, it was quite a heady time for me musically. During the week, I was studying doublebasse with an extraordinary player, Nate Hygelund. I had bought a beautiful Czechoslovakian bass in Boston and a french bow and was learning classical pieces even though Berklee was a jazz school. Looking back, what’s funny, considering Berklee has become more of a contemporary music school with strong jazz roots, is that electric bass was a non-entity at the school. It didn’t exist.

I’ll never forget near the end of the semester, Nate brought an electric bass he picked up into a rehersal room I was practicing in to ask me what I thought about it because he had no idea. He had gotten lucky. He had a weathered but beautiful Fender Precision he bought for a song. He planned to use it on some pickup gigs around town.

It was a truly amazing atmosphere to be in. I was studying arranging with Herb Pomeroy, the inspirational trumpet player and teacher, and alto sax player John LaPorta! I mean John LaPorta had played with Charlie Mingus for freak’s sakes. Pomeroy on occasion played with a faculty sextet around Boston that included Charlie Mariano, another legend who recorded on Impulse, played with many greats from that label and had been married to Toshiko Akioshi, who would later lead one of the greatest big bands in the world.

Another wonderful thing about being at Berklee was it had an extensive reel-to-reel tape section in its library on the top floor of the old building on Bolyston Street, where all the classrooms were housed. I spent hours and hours listening to everything from Coltrane to Miles to Monk to Mingus. They actually had a copy of Sgt. Pepper’s, so the school was getting hip to pop and rock, but for the most part I just absorbed all of this great jazz from the late ’40s to mid-’60s, discovering all kinds of musicians I had not been exposed to such as Eric Dolphy, who played with Trane, and John Handy, who was on some Mingus sessions as well as leading his own quintet, and so many more.

One last thing about Boston. I went to Club 47 in Cambridge that semester to see the Gary Burton Quartet, one of the first true fusion bands. Burton was an alum of Berklee who played vibes like few others. He had recruited a young guitar player, Larry Coryell, who is still one of the only players I’ve ever heard who can cross over from jazz to rock and back and not sound like he’s a jazz player playing rock. Bobby Moses was the drummer and the inventive Steve Swallow the bassist. It was definitely one of the most memorable concerts I’ve seen and believe me I’ve seen hundreds over the years. My date had to drag me out of the club after their second set because she had to get back to her dorm.

All that was during the week. On the weekend, I was in a very hip blues-rock group with my best friends. You couldn’t ask for much more.

More later.