In response to a previous post about Blind Faith, a friend expressed interest in the genesis of the infamous 1969 album cover, how it all came about.

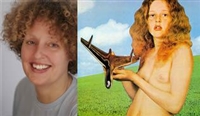

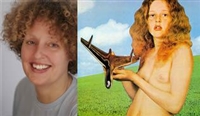

Below is a rather long excerpt from an even longer note about the creation of the Blind Faith cover by Bob Seidemann, the photographer who came up with the concept and shot the model holding the “spaceship.” To read the entire note you can go here. It’s interesting to observe that the name of the photograph was Blind Faith and that was then taken by Eric Clapton as the name of the band. Also the model was actually 11 years old at the time, Mariora Goschen. The cover is here juxtaposed with a recent photo of Goschen, who is now in her 50s, and is a massage therapist and shiatsu practitioner.

Below is a rather long excerpt from an even longer note about the creation of the Blind Faith cover by Bob Seidemann, the photographer who came up with the concept and shot the model holding the “spaceship.” To read the entire note you can go here. It’s interesting to observe that the name of the photograph was Blind Faith and that was then taken by Eric Clapton as the name of the band. Also the model was actually 11 years old at the time, Mariora Goschen. The cover is here juxtaposed with a recent photo of Goschen, who is now in her 50s, and is a massage therapist and shiatsu practitioner.

Seidemann mentions this is the first time the name of the band was not on the album cover. That’s not exactly correct. The first Stones album in England had no name on the cover and the second Traffic album also has no name. There were probably others.

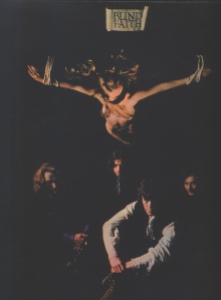

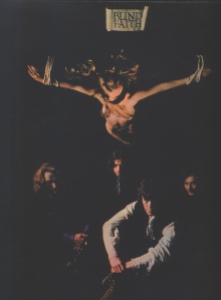

If you think the cover was an alarming image, check out this cover to the band’s tour program with a nude covered by her long hair in all the vital places blind-folded and on a crucifix.

If you think the cover was an alarming image, check out this cover to the band’s tour program with a nude covered by her long hair in all the vital places blind-folded and on a crucifix.

Another interesting tidbit is that the poster commissioned for the three Clapton-Winwood Madison Square Garden concerts in 2008 shows the spaceship, which has been likened to a hood ornament of either a 1953 Oldsmobile or 1956 Chevrolet.

The relevant portions of Seidemann’s note about the actual circumstances and how it all came about follow.

By Bob Seidemann (excerpt)

Detroit was burning. The police were rioting in Chicago, cultural icons were dropping like flies, the love generation had been kicked to death by CBS, NBC, Life, Look and Newsweek and I wanted out. I called Eric Clapton in London to ask if he would put me up for while. He did. I stayed at his flat in Chelsea with a wild crowd of ravers. The party had been going on for some time when I arrived. Other residences of the never-ending, day-for-night, multi-colored fling were Martin Sharp, a graphic artist and poet with an uncanny resemblance to Peter O’Toole, and the wildest of ravers, Philippe Mora a young film maker who looked like a cheery Peter Lorre and their handsome girl friends. I bunked on a ledge under a skylight in the living room. All of the London scene came through. It was wild and wooly.

A year passed and I had my own room in a basement flat in the same part of town with another bunch of ravers. The phone rang. It was Robert Stigwood’s office, Clapton’s manager. Cream was over and Eric was putting a new band together. The fellow on the phone asked if I would make a cover for the new unnamed group. This was big time. It seems as though the western world had for lack of a more substantial icon, settled on the rock and roll star as the golden calf of the moment. The record cover had become the place to be seen as an artist.

I had sold my cameras in San Francisco after the Pieta poster (A controversial 1967 photo that reversed roles of the famous Michelangelo painting – editor’s note)because it scared me so much, vowing never to pick up a camera again. The picture gave me the heebee jeebees and the willies all at the same time. If you pinned it to the wall, the wall would smoke. It was a picture of death alright. If I was going take up a camera again to make a cover for Eric’s new band it would have be the antidote to the Pieta image, a picture of life.

It was nineteen sixty nine and man was landing on the moon. Our species was making its first steps into limitless space and I had a shot at immortality. That’s what every artist hopes to achieve, a stab at greatness, to make something that will last for a little while. To scratch an image on a wall and hope the wall outlives him. The lights were on, the curtain was going up, and I was coming down. Down from San Francisco. Down from the height of blinding insight. Down from the top of the mountain. Down from that lofty battlefield. Down from Dr. Strangelove and 2001. The pop world was awaiting the new pop idols, and I had been asked to create their emblem.

Technology and innocence crashed through the tatters of my mind. Only a thread of an idea, something I couldn’t see, something out there just beyond my vision, an impulse rippling through the interstellar plasma. I stumbled through the streets of London for weeks, bumping into things, gibbering like a mad man. I could not get my hands on the image until out of the mist a concept began to emerge. To symbolize the achievement of human creativity and its expression through technology a space ship was the material object. To carry this new spore into the universe, innocence would be the ideal bearer, a young girl, a girl as young as Shakespeare’s Juliet. The space ship would be the fruit of the tree of knowledge and the girl, the fruit of the tree of life.

The space ship could be made by Mick Milligan, a jeweler at the Royal College or Art. The girl was another matter. If she were too old it would be cheesecake, too young and it would be nothing. The beginning of the transition from girl to woman, that is what I was after. That temporal point, that singular flare of radiant innocence. Where is that girl?

I was riding the London Tube on the way to Stigwood’s office to expose Clapton’s management to this revelation when the tube doors opened and she stepped into the car. She was wearing a school uniform, plaid skirt, blue blazer, white socks and ball point pen drawings on her hands. It was as though the air began to crackle with an electrostatic charge. She was buoyant and fresh as the morning air.

I must have looked like something out of Dickens. Somewhere between Fagan, Quasimodo, Albert Einstein and John the Baptist. The car was full of passengers. I approached her and said that I would like her to pose for a record cover for Eric Clapton’s new band. Everyone in the car tensed up.

She said, do I have to take off my clothes? My answer was yes, I gave her my card and begged her to call. I would have to ask her parent’s consent if she agreed. When I got to Stigwood’s office I called the flat and said that if this girl called not to let her off the phone without getting her phone number. When I returned she had called and left her number.

Stanley Mouse, my close friend and one of the five originators of psychedelic art in San Francisco, was holed up at the flat. He helped me make a layout and we headed out to meet with the girl’s parents.

It was a Mayfair address. This is a swank part of town, class in the English sense of the word. The parents were charming and worldly with a bohemian air. He was large and robust, she was demure. They knew the poet Alan Ginsberg, owned a tenth century manor house outside of London and were distantly related to two royal families, one English, the other German. The odds against this circumstance were astronomical and unsurprising.

Mouse and I made our presentation, I told my story, the parents agreed. The girl on the tube train would not be the one, she was shy, she had just past the point of complete innocence and could not pose. Her younger sister had been saying the whole time, “Oh Mommy, Mommy, I want to do it, I want to do it”. She was glorious sunshine. Botticelli’s angel, the picture of innocence, a face which in a brief time could launch a thousand space ships.

We asked her what her fee should be for modeling, she said a young horse. I called the image ‘Blind Faith’ and Clapton made that the name of his band. When the cover was shown in the trades it hit the market like a runaway train, causing a storm of controversy. At one point the record company considered not releasing the cover at all. It was Eric Clapton who fought for it. If this was not to be the cover, there would be no record. It was Eric who elected to not print the name of the band on the cover. This had never been done before. The name was printed on the wrapper, when the wrapper came off, so did the type.

We asked her what her fee should be for modeling, she said a young horse. I called the image ‘Blind Faith’ and Clapton made that the name of his band. When the cover was shown in the trades it hit the market like a runaway train, causing a storm of controversy. At one point the record company considered not releasing the cover at all. It was Eric Clapton who fought for it. If this was not to be the cover, there would be no record. It was Eric who elected to not print the name of the band on the cover. This had never been done before. The name was printed on the wrapper, when the wrapper came off, so did the type.

This was an image created out of ferment and storm, out of revolution and chaos. It was an image in the mind of one who strove for that moment of glory, that blinding flash of singular inspiration. To etch an image on a stone in our cultural wall with the hope that that wall will last. To say with his heart and his eyes, at a time when it mattered, this is what I see and this is what I feel. It was created out of hope and a wish for a new beginning, innocence propelled by BLIND FAITH. ©Bob Seidemann

It’s a pleasure to note that the film makers of Jeff Beck Performing This Week … Live At Ronnie Scott’s got it right. So right it’s one of the best concert films in recent memory. The last with this type of professionalism and dedication to the music and musicians was another Cream gig, the reunion concert from 2005, also at RAH. But the Beck show is better.

It’s a pleasure to note that the film makers of Jeff Beck Performing This Week … Live At Ronnie Scott’s got it right. So right it’s one of the best concert films in recent memory. The last with this type of professionalism and dedication to the music and musicians was another Cream gig, the reunion concert from 2005, also at RAH. But the Beck show is better. His influence may very well reach the furthest of the three Kings with Eric Clapton and Peter Green among his disciples. And I played with him in a one-off concert in New York in the early ’70s. But more on that later.

His influence may very well reach the furthest of the three Kings with Eric Clapton and Peter Green among his disciples. And I played with him in a one-off concert in New York in the early ’70s. But more on that later.

Cream was scheduled to play at Boston’s Back Bay Theatre in April, but they were also going to play near my hometown in New Haven at Yale’s Woolsey Hall on April 10th and I decided to come home for that, mainly because I had a new girlfriend who was still in school in New Haven. This would be our first big concert date. That made sense.

Cream was scheduled to play at Boston’s Back Bay Theatre in April, but they were also going to play near my hometown in New Haven at Yale’s Woolsey Hall on April 10th and I decided to come home for that, mainly because I had a new girlfriend who was still in school in New Haven. This would be our first big concert date. That made sense. I was having mid-afternoon waffles at a small breakfast/dinner restaurant near Kenmore Square when my buddies, one of whom was a fellow bass player from Connecticut, and I found out that Cream, yes that Cream, would be playing practically across the street at a new club called the Psychedelic Supermarket. I was astonished by my good fortune that Cream, one of my favorite bands would be in town, just a few blocks from my dorm on Commonwealth Avenue, and that they were scheduled to play for two weeks! I intended going more than once.

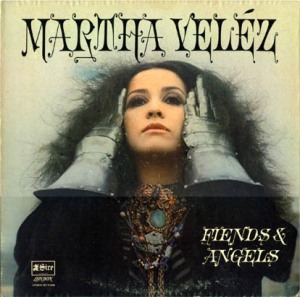

I was having mid-afternoon waffles at a small breakfast/dinner restaurant near Kenmore Square when my buddies, one of whom was a fellow bass player from Connecticut, and I found out that Cream, yes that Cream, would be playing practically across the street at a new club called the Psychedelic Supermarket. I was astonished by my good fortune that Cream, one of my favorite bands would be in town, just a few blocks from my dorm on Commonwealth Avenue, and that they were scheduled to play for two weeks! I intended going more than once. Until then, it had fetched rather pricey numbers on auction sites despite not having been a big seller at the time of its release in 1968. Still it was one of the defining blues-rock albums of the times, bringing together an almost perfect combination of singer, players and producer for a raw blues outing with unbridled energy. And some of the best playing by some of England’s best musicians.

Until then, it had fetched rather pricey numbers on auction sites despite not having been a big seller at the time of its release in 1968. Still it was one of the defining blues-rock albums of the times, bringing together an almost perfect combination of singer, players and producer for a raw blues outing with unbridled energy. And some of the best playing by some of England’s best musicians. The guitar solos are ferocious on most cuts and although Clapton is said to have played on only four, he is extremely recognizable on the heavy groove of Lightnin’ Hopkins’ Feel So Bad, I’m Gonna Leave You (perhaps the album’s best two tracks), It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry and In My Girlish Days. This was confirmed on a Velez compilation, Angels Of The Future Past, released on CD in the late ’80s. The other solos are just as powerful and inventive, perhaps attributable to the only listed guitarist on the session, Rick Hayward, although Spit James (Keef Hartley) and Paul Kossoff (Free) are said to have also participated.

The guitar solos are ferocious on most cuts and although Clapton is said to have played on only four, he is extremely recognizable on the heavy groove of Lightnin’ Hopkins’ Feel So Bad, I’m Gonna Leave You (perhaps the album’s best two tracks), It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry and In My Girlish Days. This was confirmed on a Velez compilation, Angels Of The Future Past, released on CD in the late ’80s. The other solos are just as powerful and inventive, perhaps attributable to the only listed guitarist on the session, Rick Hayward, although Spit James (Keef Hartley) and Paul Kossoff (Free) are said to have also participated. Below is a rather long excerpt from an even longer note about the creation of the Blind Faith cover by Bob Seidemann, the photographer who came up with the concept and shot the model holding the “spaceship.” To read the entire note you can go

Below is a rather long excerpt from an even longer note about the creation of the Blind Faith cover by Bob Seidemann, the photographer who came up with the concept and shot the model holding the “spaceship.” To read the entire note you can go  If you think the cover was an alarming image, check out this cover to the band’s tour program with a nude covered by her long hair in all the vital places blind-folded and on a crucifix.

If you think the cover was an alarming image, check out this cover to the band’s tour program with a nude covered by her long hair in all the vital places blind-folded and on a crucifix. We asked her what her fee should be for modeling, she said a young horse. I called the image ‘Blind Faith’ and Clapton made that the name of his band. When the cover was shown in the trades it hit the market like a runaway train, causing a storm of controversy. At one point the record company considered not releasing the cover at all. It was Eric Clapton who fought for it. If this was not to be the cover, there would be no record. It was Eric who elected to not print the name of the band on the cover. This had never been done before. The name was printed on the wrapper, when the wrapper came off, so did the type.

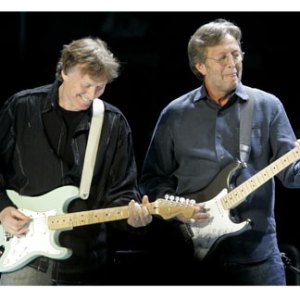

We asked her what her fee should be for modeling, she said a young horse. I called the image ‘Blind Faith’ and Clapton made that the name of his band. When the cover was shown in the trades it hit the market like a runaway train, causing a storm of controversy. At one point the record company considered not releasing the cover at all. It was Eric Clapton who fought for it. If this was not to be the cover, there would be no record. It was Eric who elected to not print the name of the band on the cover. This had never been done before. The name was printed on the wrapper, when the wrapper came off, so did the type. They had performed together in early 2007 at an English festival, Clapton joining Winwood’s touring band, and later that summer at Clapton’s Crossroads Festival in Chicago. Their set, which closed the event, had Winwood this time playing with Clapton’s band. It’s all documented on the DVD of the festival, and it’s a spectacular performance by both.

They had performed together in early 2007 at an English festival, Clapton joining Winwood’s touring band, and later that summer at Clapton’s Crossroads Festival in Chicago. Their set, which closed the event, had Winwood this time playing with Clapton’s band. It’s all documented on the DVD of the festival, and it’s a spectacular performance by both. He and his wife’s group, Delaney and Bonnie & Friends, from the late ’60s, early ’70s, never hit it really big, but had some recognizable tunes such as Only You Know And I Know. More interesting, the group featured many stars among its sidemen. Eric Clapton played with D&B following his tour with Blind Faith. Dave Mason was in that version of the group as well and George Harrison guested. Other luminaries included bassist Jim Radle, sax player Bobby Keys, now with the Stones, drummer Jim Gordon, keyboard player Bobby Whitlock and trumpet player Jim Horn and many more. Most of them played in Mad Dogs & Englishman with Joe Cocker and Leon Russell and Clapton took Radle, Gordon and Whitlock to form Derek & and Dominoes.

He and his wife’s group, Delaney and Bonnie & Friends, from the late ’60s, early ’70s, never hit it really big, but had some recognizable tunes such as Only You Know And I Know. More interesting, the group featured many stars among its sidemen. Eric Clapton played with D&B following his tour with Blind Faith. Dave Mason was in that version of the group as well and George Harrison guested. Other luminaries included bassist Jim Radle, sax player Bobby Keys, now with the Stones, drummer Jim Gordon, keyboard player Bobby Whitlock and trumpet player Jim Horn and many more. Most of them played in Mad Dogs & Englishman with Joe Cocker and Leon Russell and Clapton took Radle, Gordon and Whitlock to form Derek & and Dominoes.